The Great War followed soldiers home. British war poets Siegfreid

Sassoon and Wilfred Owen met in 1917 while both were patients at

Craiglockhart undergoing therapy for shell shock. Sassoon’s poem “Survivors” describes the

mental sufferings of soldiers who could not forget the war:

|

| French victim of shell shock reacts to officer's cap |

These boys with old, scared faces,

learning to walk.

They’ll soon forget their haunted

nights; their cowed

Subjection to the ghosts of friends

who died,—

Their dreams that drip with murder;

and they’ll be proud

Of glorious war that shatter’d all

their pride…

Men who went out to battle, grim

and glad;

Children, with eyes that hate you,

broken and mad.

What the British referred to as shell shock (the term originated in World War I), the French named variously as obusite

(from the word for artillery shell), commotional syndrome, war neurosis, or battle hypnosis. Some French physicians simply labeled the

condition hysteria, a term with a

long history that “also served to humiliate soldiers.”* French soldiers suffering from the trauma of the war faced an additional challenge:

|

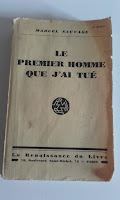

| Marcel Sauvage |

Mental illness was still too

closely tied to degenerates and drunks. While an amputee could easily be touted

as a hero, a chronically confused soldier was not a model veteran…. The

mentally alienated veterans sequestered in asylums were considered les morts vivants—‘the living dead.’

They were survivors of the war, but they were as good as dead to their families

who saw them rarely and could no longer count on them for financial or

emotional support….Even those who escaped institutionalization were seen to

inhabit a realm that was somewhere short of truly living.**

Marcel Sauvage was nearly nineteen when the war interrupted

his medical studies in Paris. Serving as a stretcher bearer at the Somme,

Sauvage was seriously injured and gassed while recovering the wounded. A French newspaper commended his courage,

describing him as a “stretcher bearer of absolute devotion” (brancardier d’un dévouement absolu).† Sauvage’s war poems were written between 1916

and 1920; his poem “Recall-Up” (Rappel) depicts memories that

tortured many of the veterans of the First World War. The poem’s title carries

a double meaning, suggesting the act of remembering as well as that of summoning

the troops (in French, battre le rappel).

Recall-Up

Suppose, all at once,

Blood were to bead

From mahoganies

And walls and hangings

Suppose, in the night, all at once

The lamps bled,

Lights like wounds?

Or your rugs swelled and

Or your rugs swelled and

Exploded, like bellies of dead horses?

Suppose the violins

Took up

The tears of the men,

The last refrain of the men

With exploded skulls across every plain on the globe?

Suppose your diamonds, your bright diamonds,

Now were only eyes

Madness-filled

All round you, in the night,

All at once?

What would you tell of life

To a skeleton, suddenly there,

Stock-still, bone-bare,

Its only mark

A Military Cross?

--Marcel

Sauvage, translated by Ian Higgins

The poem begins by inviting readers to imagine or dream—“Suppose”—

but the visions that follow lead on a journey into madness. Spreading out from the trenches, the war has polluted the very sanctity of home. Blood wells up

from drawing room furniture and drips from curtains and walls; lamps bleed

“like wounds,” and rugs bloat like the carcasses of dead horses until they

explode under the internal pressure. Domestic objects of comfort and beauty are

transformed into hallucinations of horror, and even the glitter of diamonds shifts

to reveal glowing eyes of madness that stare out from the dark.

Sound is also distorted, as the music of violins sobs with the

last refrain of men dying horribly, their skulls exploded by machine gun fire,

shrapnel, and shell. In the poem’s final chilling image, we stand before the

skeleton of a dead French soldier who stands bone-bare, wearing only his medal of

bravery, the Croix de Guerre. What can we tell him of life, we who have inhabited the haunted minds of les morts vivants—‘the

living dead’?

Sound is also distorted, as the music of violins sobs with the

last refrain of men dying horribly, their skulls exploded by machine gun fire,

shrapnel, and shell. In the poem’s final chilling image, we stand before the

skeleton of a dead French soldier who stands bone-bare, wearing only his medal of

bravery, the Croix de Guerre. What can we tell him of life, we who have inhabited the haunted minds of les morts vivants—‘the

living dead’?

In 1929, Sauvage published Le Premier Homme Que J’ai Tué (The

First Man I Killed). The book recalls

how at the age of twenty, a young soldier thrusts his bayonet into the body of

a German soldier and watches him die. For

many of the soldiers of the Great War, the battles continued to rage long after

the Armistice was declared and the Treaty of Versailles was signed. Theirs was a war that never truly ended.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

*Gregory M. Thomas, Treating the Trauma of the Great War:

Soldiers, Civilians, and Psychiatry in France 1914-1940, Louisiana State

University Press, 2009, pp. 20-21.

** Thomas, Treating

the Trauma, pp. 125-126.

††Many thanks to Ian Higgins for generously discussing his translation of the poem and for granting permission to include it on this blog.