|

| Red Cross, St. Louis October 1918 (National Archives) |

In September of 1918, a physician wrote from Camp Devens, Massachusetts, “It is only a matter of a few hours … until death comes and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible. One can stand to see one, two, or twenty men die, but to see these poor devils dropping like flies gets on your nerves. We have been averaging about 100 deaths a day, and still keeping it up.”* Colonel Victor C. Vaughan, former president of the American Medical Association, also visited the US military camp and reported, “In the morning the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cord wood. This picture was painted on my memory cells at the division hospital, Camp Devens, in the fall of 1918, when the deadly influenza virus demonstrated the inferiority of human interventions in the destruction of human life.”*

Some Americans thought that the 1918 influenza virus was a German weapon of war, released by enemy agents who had arrived in Boston with vials of the germs; others suspected that the German pharmaceutical company Bayer had mixed the virus into aspirin.* German propaganda blamed the illness on Chinese laborers employed by the Allied Powers.”**

By the end of the world-wide pandemic, at least 20 million had died; estimates range from 20 – 100 million, with most experts believing more than 50 million were killed by the virus. What became known as Spanish Influenza was particularly fatal to healthy adults between the ages of 20 and 40.

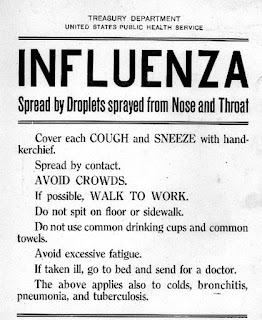

With no known cure, most efforts were directed at stopping the spread of the illness. Historian David McCullough writes, “In Boston the stock market closed. In Pennsylvania a statewide order shut down every place of amusement, every saloon. In Kentucky the Board of Health prohibited public gatherings of any kind, even funerals.”*** And an Albuquerque New Mexico newspaper wrote, “the ghost of fear walked everywhere, causing many a family circle to reunite because of the different members having nothing else to do but stay home.”†

In the chaos and uncertainty that accompanied the virulent pandemic, lists of practical health guidelines were published in nearly every major newspaper. One writer used poetry to spread the message:

Rules for Influenza

Oh, shun the common drinking cup,

Avoid the kiss and hug,

For in them all there lurks that Hun,

The influenza bug.

‘Tis neither kind nor neat,

Because it scatters germs around.

So try to be discreet.

Lick not the thumb in turn o’er

The papers in your file,

And wear your health mask, though you look

Like time. Forget it. Smile.

Remember doorknobs harbor germs,

So wash before you eat.

Avoid the flying clouds of dust

While walking on the street.

Most anything you do—or don’t—

Is apt to cause disease,

So don’t do anything you do

Without precautions, please.

—Dr. Waters (Chemistry)

|

| Nurses in Boston, National Archives |

The poem’s author, Dr. C.E. Waters, worked during the First World War at the Bureau of Standards as chief of the Organic Chemistry section. Prior to the war, he had taught at Connecticut Agricultural College and Johns Hopkins University. The poem appears in The Great War at Home and Abroad: The World War I Diaries and Letters of W. Stull Holt. In a letter dated October 25, 1918, Holt’s fiancée, Lois Crump, included the verse with the note, “I am enclosing some stuff which may make you laugh” (Crump worked at the Bureau of Standards).††

Little has changed in preventing the spread of viral pandemics. Dusty streets and common drinking cups are no longer common, but hand-washing, avoiding close contact, staying at home, and using humor to cope with uncertainty and fear remain very much the same.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* Gina Kolata, Flu, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999, p. 14; p. 16, p. 3.

** J.N. Hays, Epidemics and Pandemics, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p. 390

*** David McCullough, “Foreword” in Lynette Iezzoni, Influenza 1918, TV Books, 1999, foreword, p. 7.

† Kolata, p. 23.

†† Maclyn P. Burg and Thomas J. Pressly, editors, The Great War at Home and Abroad: The World War I Diaries and Letters of W. Stull Holt, Sunflower UP, 1998, p. 263.